‘Recoverist = Recovery + Activist’. So reads the text either side of ‘Recoverist Curators’, a new exhibition in The Whitworth’s project space, running until June 2026. Spearheaded by Portraits of Recovery – ‘a Manchester-based visual arts charity supporting people who identify as being in recover from substance use’ – this exhibition makes good use of natural and authentic voices to contextualise a somewhat unfocussed collection of art.

As the result form a yearlong project, this exhibition is admirable. The Whitworth’s collection has been explored and selected from in a deeply personal manner. The first thing I notice is how sincerely this exhibition has given agency to its Recoverists. The Recoverists are billed as curators, not as co-curators or participants, and their voices are present and clear throughout.

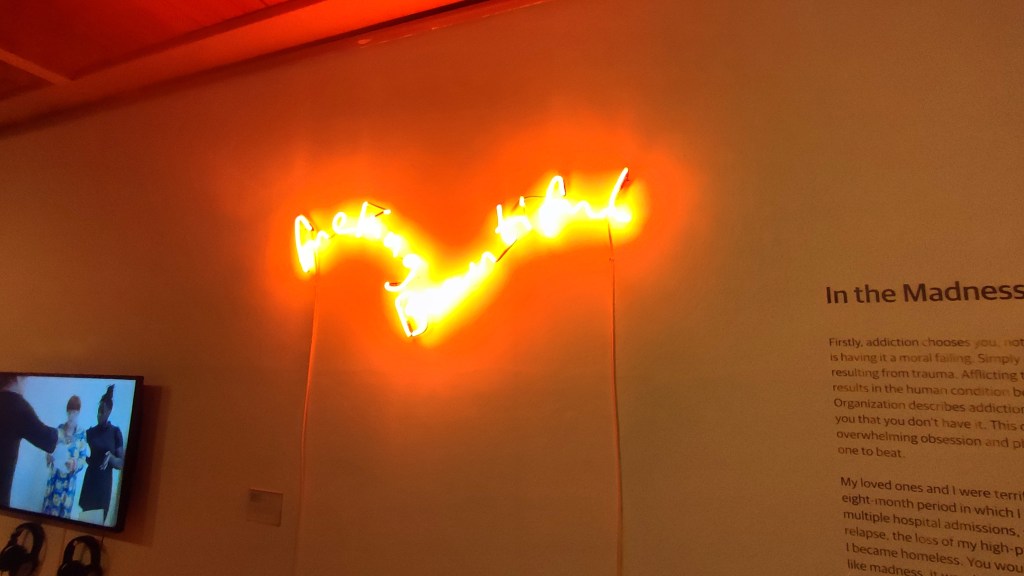

The exhibition is structured into three themes: ‘In The Madness’, ‘Keep(ing) it Simple’, and ‘Self Love’. I am first drawn to an artwork which appears to straddle both ‘In The Madness’, and ‘Self Love’: T. Noble and S. Webster’s fuckingbeautiful (detail), 1998.

The intensity and warmth of the red light is overwhelming, and my poor phone camera cannot capture it very well, but it’s siren-like draw punches out across the gallery space. Up on the mezzanine it is rather warm, even more so under this light.

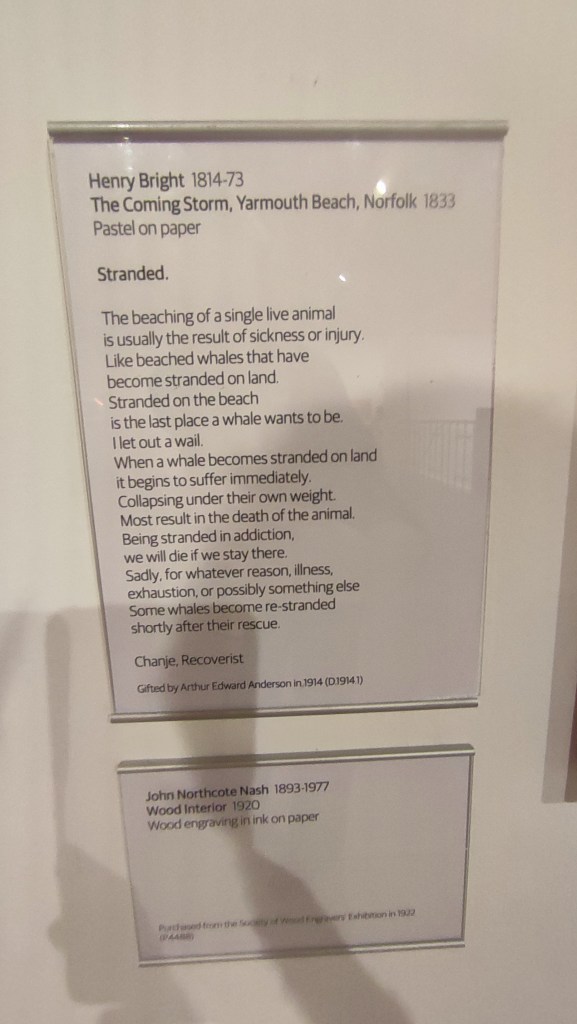

Moving to ‘In The Madness’, I note how each and every instance of text – barring the opening spiel – is written by and accredited to one of the Recoverists. Object labels contain the usual provenance, but are followed by a personal reflection, a story, or even a poem from one of the curators. Unlike the standardised, formal – and occasionally sanitised – label text one would expect from the Whitworth, there appears to have been little to no edits made. This leaves the Recoverist’s voices intact. Lengthy sentences, peculiar syntax and reflection only tangentially linked to the artworks in question re-affirm the humanity and realness of these blocks of text.

On occasion, the text accompanying an artwork is a touch too long, and a visitor expecting to engage more with the artworks themselves may struggle. Yet, these personal, honest, and emotional justifications for the selection of the works on display centres the curators as the main reason for the exhibition. The art is supplementary; it is a vehicle to allow for connection and the telling of stories.

That said, the artworks themselves are at time uninspiring. While they function mechanically as aspects of a theme, they have little in-and-of-themselves. Lacking any clear visual continuity or connection beyond the theme provided by the exhibition, they appear somewhat disorganised. Their relation to the Recoverists is clear and worthwhile. Their relation to one another, less so.

In the centre are two cabinets. One holds Caroline Bartlett’s Conversation Pieces (2003). They seem unconnected to any of the three stated themes but are visually engrossing and a very pleasant, tender, inclusion. The other cabinet holds personal items from the Recoverists, as well as artworks they have created. This deepens the connection to the curators and is a nice three-dimensional counterpoint to the works on the walls. Again, the objects themselves are secondary to the stories they enable.

Within this second cabinet we find the brilliant quote from Dom P. – ‘I used to think my creative heroes were great because they were addicts, now I realise they were great despite being addicts’, alongside a copy of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas.

The most interesting aspect of the exhibition is the ‘Keep(ing) it Simple section. Wallpaper (R. Ryan’s We Had Everything (2014)) is used to block off a corner of the room, transforming it into a domestic setting. When viewed from one angle it works incredibly well, instilling a different sense of calm from the usual gallery atmosphere. The room is furnished with a sofa, carpet, desk and chair. Upon the desk is a list of places you can go to seek support, as well as a place to share thoughts and reflections.

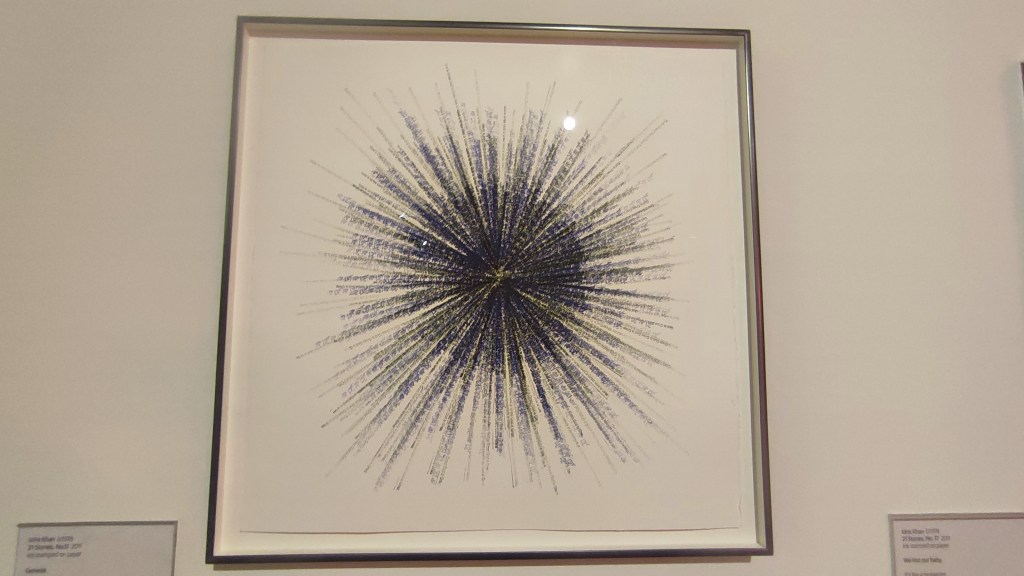

It could be argued that the slight disorganisation of the majority of the gallery is reflective of the themes, since the ‘Keep(ing) it Simple’ section is, indeed, more simple, refined, and focussed. Within this section we find my favourite work of the exhibition: Idris Khan’s 21 stones (2018). These three works are each accompanied by poems by one of the curators, Chanje.

Overall, while the thematic core and purpose of this gallery is clear and effectively delivered, a visitor may not get as much out of this as the team that put it together. With dense text panels and slightly unfocussed works, this exhibition is best seen not as a vehicle to see art, but as a thoughtful, personal, and honest product of an brilliant yearlong project.

‘Recoverist Curators’ is on at The Whitworth between 25 July 2025 – June 2026 and is, as ever, free to enter.

Leave a comment