The Turner Prize, 2025, continued…

Leaving behind Zadie Xa and Rene Matic, I ascend to the first floor. Immediately, there is an obligatory section detailing the history of the prize. It is quite entertaining to take a whistle-stop tour of the previous winners. Many people are spending as much time with this section as they are with each of the four installations. Unsurprising. It is engaging, varied, and far easier to engage with.

I take the path to my right.

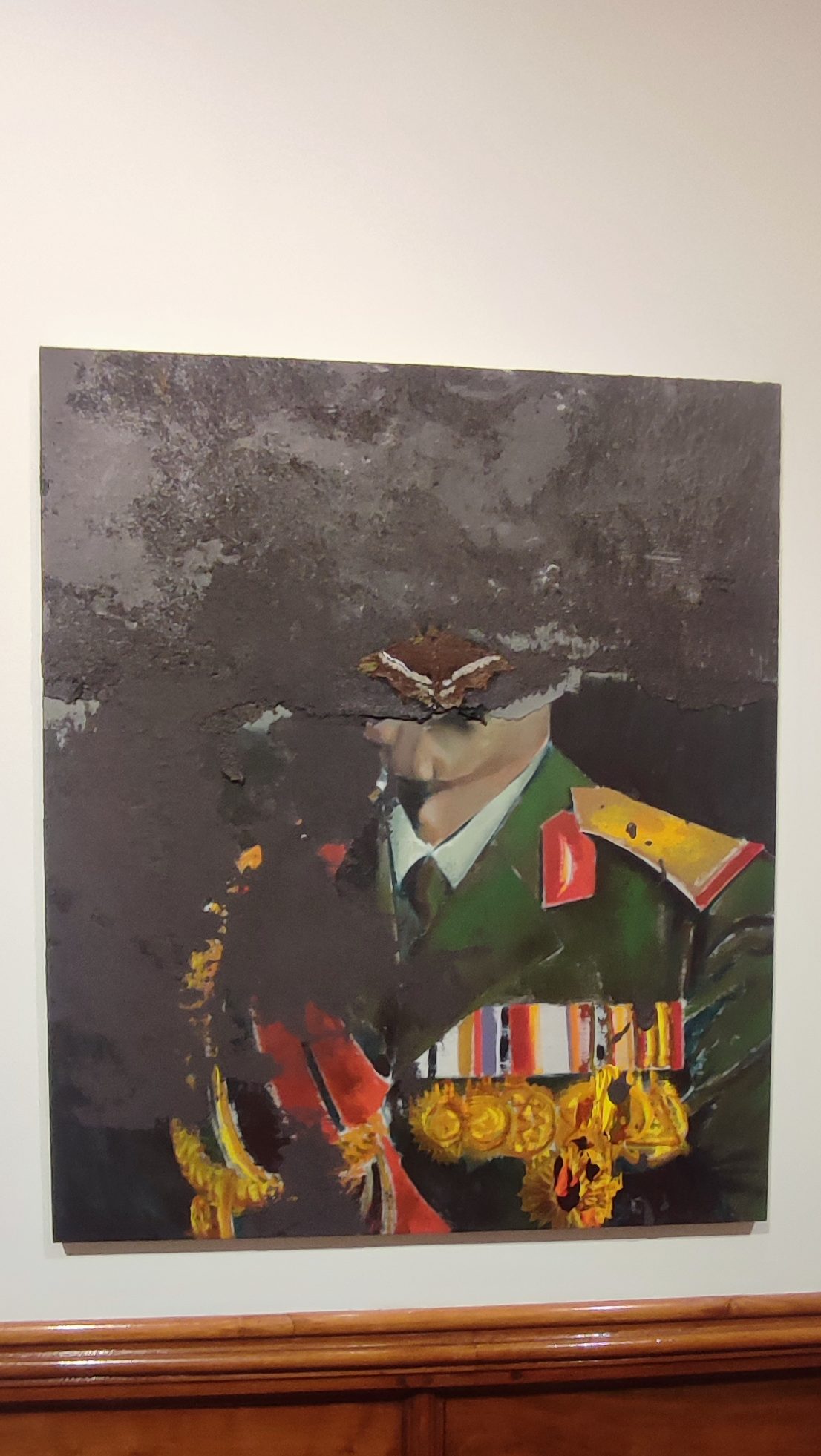

In a relatively sparse room – white walls and wooden floor creating nothing more than the customary gallery environment – I find Mohammed Sami. He is nominated for an exhibition previously held in Blenheim Palace. The shift in context is crucial to an appreciation of his work.

The walls hold large canvasses – meters long and high. Barring one portrait, itself obscured, there is a distinct absence of human figures in his artwork. Despite that, signs of their presence remain. Without any graphic depiction of violence, his art is full of its implication. Look too long at a work and it becomes quite challenging – at least it did for me.

Titles hold a lot of narrative weight here. A painting of a trampled field, rife with hoofprints, is entitled Massacre. The weight imparted by these framing titles is quite astounding. In others, the violence, or the potential of violence, is more apparent. Lasers, sightlines, cut across a scarred land, the horizon seems on fire.

Hiroshima Mon Amour appears to depict clothes, floating under water, holding the shape of human form. The surface is concave, indented by what one can only assume is the force of a nuclear explosion, given the title. It is a deeply upsetting image. As if we have all gone, and all that is left of our achievements, our struggles, is the violence that we have brought into the world.

At first, I was not taken by the works. I span around the room, taking in the artwork, and musing smugly to myself at the reactions of fellow visitors. On multiple occasions, people would approach a gallery attendant and ask ‘so, what does this one mean?’, ‘what is this supposed to be?’ only for the attendant to try their best to explain the inherent interpretability of the visuals. Since they are not abstract – clearly figurative, if not fully realistic – then they must have a singular meaning.

However, taking a moment to sit with The Grinder, I experienced a definite shift. I felt as if I was falling. The orientation of the perspective, the mystery of the shadow object taking up the frame, the faded floor. It made me decidedly upset – the sort of prickling anger one feels at helplessness. Spending time with this painting allowed me to revisit the room and give enough time to each of the images.

Before visiting, I assumed that Sami would be far from my favourite – my predilection for sculpture over painting clouding my judgement – yet tapping into the depth they held – even for a short moment – really swung me.

Doubling down on my vote for Sami, I found out, after leaving, that each artist has a reading list. While the other three artists have a good range of texts and music, Sami has three texts by Emil Cioran and three texts by Arthur Schopenhauer. Driven, directed, and arguably very pessimistic. I just wish I could have seen his paintings in the context of Blenheim Palace. I can only imagine how strong and affecting that would have been.

Our final exhibiting artist is Nnena Kalu. The Guardian’s favourite to win. Another site-specific set of artworks now re-displayed in Cartwright Hall. Forms hang suspended. Around the walls, sets of spirals hang in pairs or threes.

The works on paper, at first sight, look little more than a large spirograph, printed twice. However, on closer inspection, each work is unique. The matched pairs have been created to look almost identical. Each bare the marks of their maker. Noticing that each work is unique, yet at a glance identical, re-framed them as highly intentional. The replication of process questions the randomness of the lines. At no point are we told which one was created first. Theoretically, any of the spirals could be the original, the other the copy. They are interesting, visually intriguing, and hold space for exploration.

The sculptural work, beautiful and lively as they are, are out of place. They appear as if frozen mid movement. It is almost bizarre seeing them stationary. Each is composed of many strands of ribbons, plastic, materials woven around a central tube. There is an element of shibari to them, bound and contorted, suspended in an artful way. They feel alive and curious.

However, Nnena’s work, we learn, is in response to specific environments. Gutted buildings, post-industrial spaces full of new energy. Almost the exact opposite of here. It is like visiting a zoo rather than a safari park. Their works seem caged, restrained by the room they find themselves in.

As colourful and ingenious as her works are, they are left to deflate in this exhibition. I am surprised at the Guardian’s praise of her. Perhaps they have encountered Nnena beforehand, hence their high esteem.

Which brings this review of the Turner Prize, 2025, to an end. Mohammed Sami is my favourite, yet overall, the artists were somewhat tame – not toothless, only provocative in a very known manner. As is the way with any exhibition of this scale, the impact would have been greater, were it to be a solo show. My main takeaway is the fact that Sami’s After the Storm exhibition at Blenheim is yet another stop on a hypothetical time travel art tour. I will keep an eye out for when the winner is announced.

Leave a comment